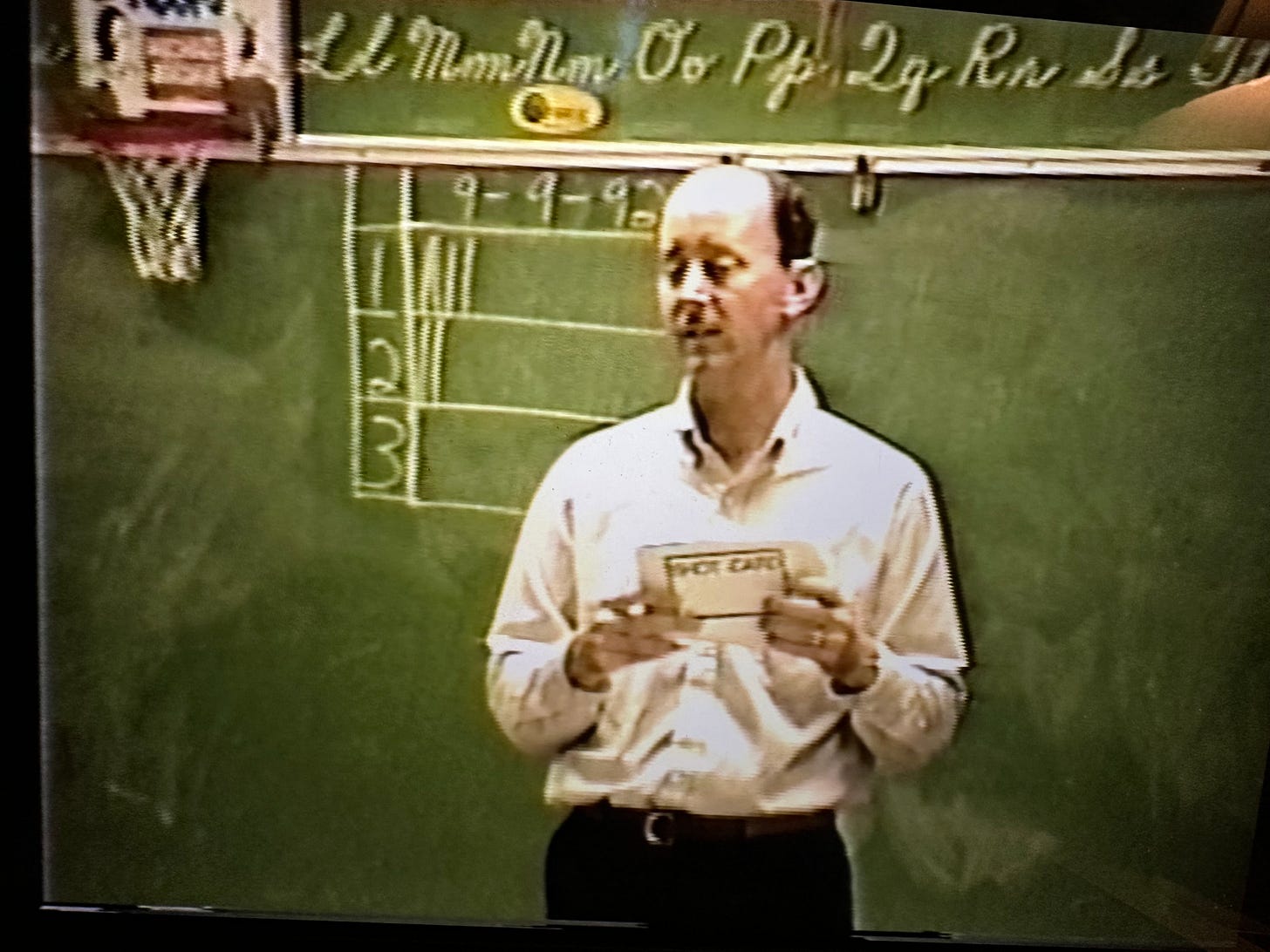

Mr. Frank Verga, Teacher, Encinitas School District, describing LearnBall.

As I mentioned in previous posts, I consulted with numerous school districts in Southern California. Usually, the Director of Special Education or the school's principal would call me and ask if I would help a teacher with a particular student or group of students. Sometimes a student’s behavior was the issue, sometimes the teacher needed help in managing her classroom, sometimes it was both. However, for today’s post, I will discuss the time I went into a well-run teacher’s 5th-grade classroom and learned something I did not know before, Learnball. It was more than fab.

Learnball is a classroom management system, similar to The Good Behavior Game, but it inserts a version of basketball played inside the classroom to improve its effectiveness and make it more fun.

The Good Behavior Game

In the original Good Behavior Game (Barrish, Saunders, & Wolf 1969) a 4th-grade class was divided into two teams, matched for academics, and behavior problems. Students were told that if they misbehaved by talking out or leaving their seats their team would receive a checkmark on the blackboard. The team with the fewest checkmarks won the game that week and received a prize such as extra recess time, or extra privileges or earned free time at the end of the day. If both teams obtained less than 5 checks in the week, both teams won and received their rewards. Appropriate behavior was reinforced, also, with praise and attention. Since 1969 there have been several variations of this game used in classrooms all over the country.

Daniel Tingstrom, Heather Sterling-Turner, and Susan Wilczynski (2006) wrote a review of the literature from 1969-2002. They list 29 research articles that demonstrate the effectiveness of the Good Behavior Game on behavior and academic achievement.

Disadvantages. According to Tingstrom et al., (2006), peer pressure that operates when group contingencies are used is an important disadvantage to mitigate. Children may harass those members of the team that do not behave well in class, do not complete their assignments, or vice versa. Students on the losing team may think it is unfair and retaliate. To mitigate those possibilities, “Talking and role-playing with students about how to react when they are on the losing team was helpful”. (Davis and White 2000). Also, making sure that both teams win about equally over the school year (by balancing the team members) mitigates the sense of unfairness that may arise if one team dominates another.

Learnball

I observed Mr. Verga, a 5th-grade teacher at Flora Vista Elementary School in Encinitas, use Learnball in his classroom. As I mentioned, it is similar to the Good Behavior Game, but much more exciting and fun.

Verga had about 30 students in his classroom. During the first two weeks, he ran his classroom without Learnball. During those two weeks, he observed his students with the idea of forming 3 equal teams. He considered classroom behavior, academic performance, and physical coordination (how well can they toss a ball into a hoop).

Teams. At the end of the two-week assessment period, he divided his students into 3 teams: 1,2, and 3. and explained the game to his students. He reserved the ability to rebalance the teams again if he felt the teams were unmatched. He placed the students’ desks in rows. He assigned students to their seats. The first two rows were Team 1, the next two rows were Team 2, and the next two rows were Team 3. Each team elected a president and a vice president should the president be absent. A Nerf basketball hoop that could be easily detached was affixed to the wall in front of the class.

SHOT Cards. Mr. Verga had about 60 index cards with the word “SHOT” on them, aka shot cards. On the blackboard, there were three boxes drawn, one for each team where Mr. Verga kept track of the points scored during the game. When students came into class, he collected their homework assignments. Each student received a shot card when they handed in their work. The student then passed the shot card to the team President, who kept them until the “shoot out” was played each day at 11:30 am before lunch and at 2:30 pm, 30 minutes before school ends. During class, if a student gave the correct answer, was on task, completed an assignment, asked a question, or engaged in some positive behavior Mr. Verga identified the student with praise, then gave the president of the student’s team a shot card. On the other hand, If a student on Team 1 did not complete the assignment, was off task, did not turn in homework, or was mean or rude to another student, Mr. Verga identified the misbehavior and gave a shot card to the other two teams. This continued throughout the day until the 11:30 shoot-out, and again at the 2:30 shoot-out.

The Shoot Out. Mr. Verga separated the desks so there was an empty row directly in front of the small basketball hoop. Masking tape was placed on the floor at 1ft, 2ft, 3ft, 4ft, 5ft, and 6ft away from the hoop. If a student stood at the 1ft line and tossed the small spongy ball into the hoop they earned 2 points for the team. Two-foot shots earned 4 points, 3ft shots earned 6 points, and so on. The team with the fewest shot cards went first. Let’s imagine that at 2:30 pm, Team 1 earned 10 SHOT cards, Team 2, 8 SHOT cards, and Team 3, 12 SHOT cards. Each president held the cards. The president decided who shot from which line. He or she might put a small student 2 feet away, and another student 5 or 6 feet away. Close shots were more certain to go in the hoop, and shots farther away were more difficult. Each president managed his team. The strategy of the game helped make it fun. Mr. Verga began the shootout. Team 1 went first. Team 1 obtained 30 points, Team 2 received 35 points, and Team 3 earned 29 points. Team 2 won that day. Mr. Verga recorded the win and gave the team a TEAM Card. By Friday all teams won games and earned TEAM cards. However, Team 2 won more TEAM cards than the other teams that week. So, they received a pizza party on Friday, where the winning team ate pizza, listened to music, and practiced their shot-making abilities. Plus, the members of the winning team were bestowed special privileges for the following week.

Permit me to summarize the reinforcement contingencies again. When the student behaves well and completes assignments, his or her team gets a shot card. When students misbehave the two other teams receive SHOT cards. The more shot cards earned the more shots at the basket the team can take, the greater the chance the team will win the “shoot out”. There are two shootouts per day. The winning team obtains a TEAM card. The team that obtains the most TEAM cards each week receives a pizza party on Friday.

It’s hard for me to describe the joy and enthusiasm I observed during typical class days, when the students were working in class, and particularly when they were playing the game. Both boys and girls loved it. It was fantastic.

Aftermath

Mr. Verga became a very popular teacher in the district. He won the Teacher of the Year award after he introduced Learnball to his class. About a year later I was hired by the district to help two teachers, one in special education and one in general education, use Learnball. The general education teacher was enthusiastic about the program but thought it was a lot of extra work, and it prevented her from using some of her favorite teaching techniques. However, she was pleased with how the program reduced behavior problems in class and increased the motivation of her students to complete their work. The special education teacher refused to visit Mr. Verga’s class to see how Learnball operated. She did not want to use group contingencies. She did not want to run a program with so many overt artificial reinforcers. She disliked almost everything about Learnball, particularly the shot cards. So, we worked on individual program plans for the students she identified.

I retired about 8 years ago. Mr. Verga retired from the district several years ago. Today no teacher in the Encinitas School District uses Learnball. In my 30 or so years working in school districts in California I did not find another teacher who used Learnball. In fact, I’ve discovered that a teacher, Diane Murray from the Pittsburg Public School District, was told she was forbidden to use Learnball in her class (1996). She sued the district on first amendment grounds but was not successful.

I’m sensing a recurring theme: behaviorally oriented teaching strategies that are particularly effective are not used frequently by teachers across the country. There appears to be a backlash against their use. Why is that, I wonder? A topic for a future post, perhaps.

Should All Teachers Use Learnball In Their Classrooms?

No. I would encourage teachers to use Learnball if they were so inclined. I would not require it in our imaginary elementary school. Many classroom management techniques work. Compared to the Good Behavior Game, Learnball is more fun, but more complicated to operate. It is not easy to deploy in a classroom. Unfortunately, there is not a lot of research on the effectiveness of Learnball on academic achievement. There is extensive research on group contingencies which makes me believe Learnball can be an effective and fun classroom management system.

References

To learn more about Learnball visit: https://www.learnball.com/

Barrish H.H., Saunders, M., & Wolf, M. W. (1969) Good Behavior Game: Effects of Individual Contingencies for Group Consequences on Disruptive Behavior In A Classroom. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 2, 119-124

Diane MURRAY, Plaintiff,v. PITTSBURGH BOARD OF PUBLIC EDUCATION, Lee B. Nicklos, individually and in her capacity as Director of Human Resources, and William Nicholson, individually and in his capacity as a Principal of Letsche Education Center, Defendants. Civil Action No. 94-2157. United States District Court, W.D. Pennsylvania. March 25, 1996. https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/919/838/1581013/

Tingstrom, D., H. Sterling-Turner, H., & Wilczynski S., M. (2008) The Good Behavior Game: 1969-2002. Behavior Modification 30 225. http://bmo.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/30/2/225